TAKEAWAYS

In a previous article, I explored the necessity of a shift in Singapore’s approach to community development in response to evolving societal demands. In this article, I build upon that discussion by introducing a practical framework for implementing asset-based community development (ABCD), tailored to the Singapore context.

Before delving into the specifics of the framework, it is crucial to first comprehend the reasons for a re-examination of traditional ABCD models. While the original theory presents compelling principles, its effectiveness is constrained when applied without adaptation to local realities. A contextualised approach ensures that community-building endeavours are both pertinent and enduring.

Through our research with the People sector, we have discovered that Singapore’s approach to community development is undergoing a fundamental transformation. This shift is driven by three key challenges, namely, limited resources, a lack of continuity in initiatives, and rising citizen expectations.

1) Limited resources

Limited resources have exerted increasing pressure on the Public and People sectors to accomplish more with fewer resources. Community initiatives, particularly those led by social service agencies (SSAs), have traditionally relied on government funding. As Singapore reorients its fiscal priorities, it is imperative for the People sector to adopt more self-sustaining and efficient methods.

2) Lack of continuity

There is often a lack of continuity in community projects. Without genuine ownership by residents, initiatives often falter once the initial support from government or agencies diminishes. This engenders a cycle of dependency that necessitates continuous injections of resources such as financial and human capital.

3) Rising citizen expectations

Citizen expectations are evolving. Residents now demand services that are not only effective but also prompt and affordable. Given finite resources, this necessitates a shift towards more participatory, targeted, and sustainable development models.

Given the challenges that Singapore faces, a new approach to community development is necessary. During our discussions with the People sector, one such approach mentioned was ABCD. However, upon reviewing traditional ABCD models, several challenges were identified that hinder their effective implementation, particularly in areas of coordination and alignment, local resource availability, and progress pace.

1) Coordination and alignment

Regarding coordination and alignment, traditional ABCD assumes that community members are both willing and able to contribute actively. However, in practice, the diversity of views and interests within a densely populated community can lead to conflicting opinions, making it difficult to establish a unified direction without excluding or alienating certain groups.

2) Local resource availability

The availability of local resources poses a significant barrier. While ABCD is based on the premise that communities possess sufficient internal assets to address their challenges, this assumption may not always hold true. In some cases, the necessary expertise, facilities, or manpower may simply not exist within the community, necessitating external support. Adhering strictly to a purist interpretation of ABCD may therefore be impractical in such contexts.

3) Pace of progress

The slow pace of progress is a notable concern. Traditional ABCD approaches are heavily ground-up and consensus-driven which, while inclusive, often result in prolonged timelines. The time required to build alignment, develop shared goals, and mobilise stakeholders can span several years. In Singapore’s fast-paced environment where outcomes are often expected within months, such timelines may not be feasible.

Given these limitations, there is a compelling need for a Singapore-specific approach to ABCD, one that is attuned to our national context and operational realities. Our adapted definition of ABCD is “the capacity to foster community cohesion, establish relationships, and initiate actions to effect positive transformations within a community”.

This approach was developed as a result of our research, which consisted of discussions with various key members of Singapore’s People sector. It draws upon Singapore’s longstanding belief that the family forms the bedrock of society, while acknowledging the growing necessity for robust and resilient communities in the face of evolving family structures. By synergistically combining local strengths with structured coordination, this rendition of ABCD supports targeted, community-driven solutions without compromising the clarity and efficiency required to meet contemporary demands.

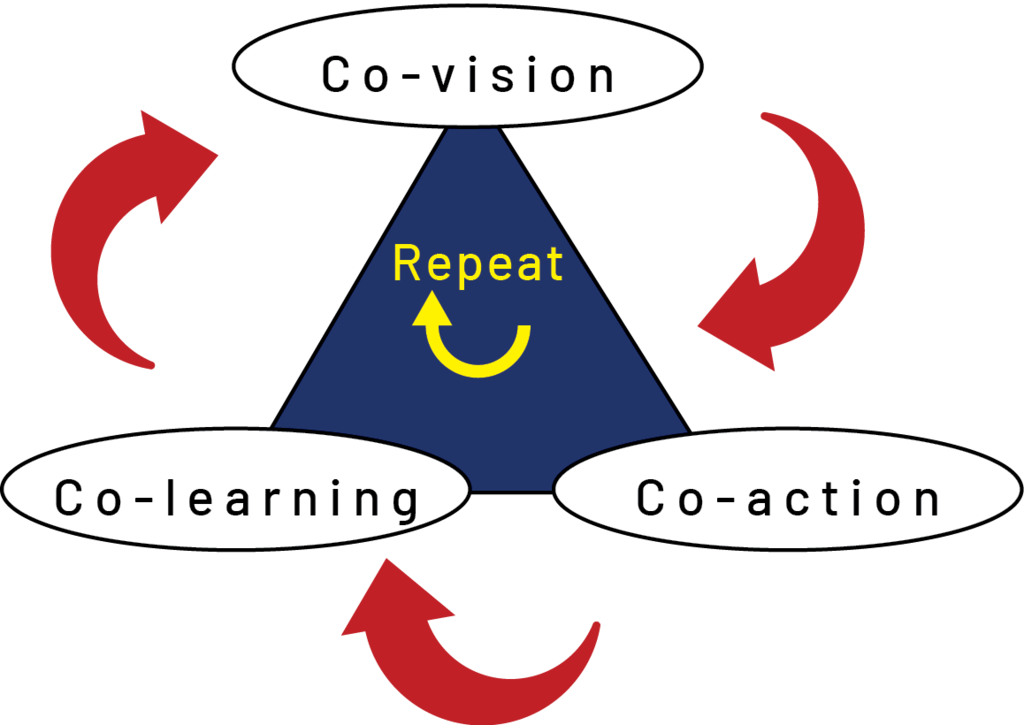

Our theoretical framework for ABCD posits a three-tier process which encompasses co-vision, co-action, and co-learning (Figure 1). This iterative process is explicitly encouraged for communities to adopt.

Figure 1 Co-vision, co-action, and co-learning for community development

1) Co-vision

Co-vision is the process of developing a shared vision for the community – a vision that is collectively shaped and widely accepted. This process is divided into two key stages: community groundsensing, and community co-visioning.

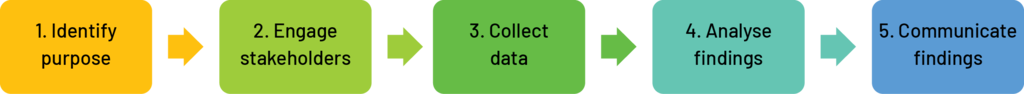

Figure 2 Co-vision: Community groundsensing standard operating procedure (SOP)

Community groundsensing is a systematic process for understanding community needs, strengths, and sentiments (Figure 2). It begins with defining the project’s purpose to ensure clarity and relevance, followed by engagement with the stakeholders of the project. Stakeholder engagement is then prioritised to capture diverse voices and build inclusivity. As part of this step, the team would also need to identify the required data, to avoid unnecessary collection.

Data collection is designed using appropriate methods, such as surveys, interviews, or focus groups, and informed by prior groundwork. Both quantitative and qualitative data are gathered and analysed to extract insights into community concerns and aspirations. Analytical tools, such as fishbone diagrams, help identify root causes of social issues, while statistical charts illustrate patterns. The final stage involves communicating the findings and exploring next steps. Results can be shared through informal sessions (for example, coffee chats) or digital platforms (for example, community WhatsApp groups). A key principle is ensuring feedback reaches even the “silent majority”, who may not participate directly but value being informed and included in decision-making.

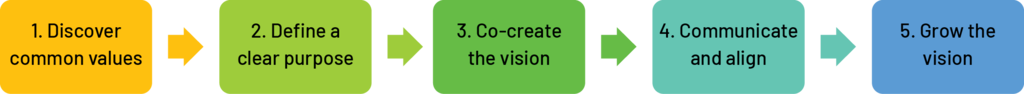

Figure 3 Co-vision: Community vision SOP

Community co-visioning is the second stage of co-vision, where residents come together to articulate a shared vision based on insights from groundsensing (Figure 3). The process unfolds in five steps.

First, common values are identified through a reflective process led by a core committee representing the Public, Private, and People (3P) sectors. This step establishes the principles that unite the community. Next, the group defines a clear purpose, clarifying why a vision is needed, and aligning objectives to avoid wasted effort. With values and purpose in place, the committee facilitates collaborative vision creation. Using tools such as the marketplace workshop plan, participants organise groundsensing data and personal experiences into thematic categories. Divergent thinking encourages the wide exploration of ideas, while convergent thinking refines them into a unified draft vision.

The draft is then communicated to the wider community for feedback, sparking dialogue and building ownership. Insights are reviewed, incorporated, and used to revise the vision. Finally, the vision is expanded until sufficient community support is achieved, typically with at least 30% endorsement. Once consensus is reached, the vision is formalised and widely disseminated to guide subsequent action.

This process balances top-down structure with bottom-up participation, ensuring the vision is strategically coherent while resonating with community values. Such hybridity strengthens legitimacy and enhances prospects for sustained success.

2) Co-action

Co-action refers to the process of transforming a shared community vision into a concrete action plan that enables residents to work together meaningfully. This stage is divided into two key phases: community asset mapping and community mobilisation.

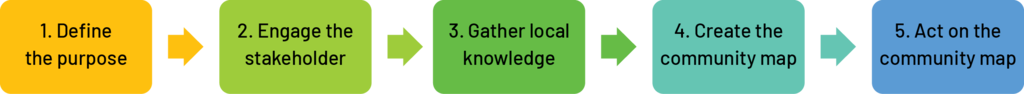

Figure 4 Co-action: Community asset mapping SOP

Community asset mapping (Figure 4) marks the first step of the co-action process. This strength-based exercise identifies and organises existing resources within the community, fostering an empowering perspective by focusing on assets rather than deficits.

The process begins with defining the purpose of the mapping exercise, ensuring that objectives are aligned with community goals, and resources are used efficiently. A core committee, often the same group involved in co-visioning, is then convened with representation from the 3P sectors.

Data collection draws on local knowledge through interviews, observation or surveys, to capture both tangible and intangible assets ranging from skills and facilities to informal networks. These insights are then translated into a visual community asset map, using photographs, block diagrams, or digital tools such as Google Maps. Symbols, shapes and lines can be employed to denote resource scale and the strength of relationships between assets, thereby revealing spatial patterns, resource clusters, and service gaps. For example, identifying a concentration of elderly residents in a block without nearby services may highlight a priority area for intervention.

Once assets are mapped, the tool is refined and implemented. The map guides project development, highlights areas of opportunity, and is continually updated as understanding deepens. Findings are presented back to the community through facilitated discussions, to validate the data and determine next steps.

A key outcome of asset mapping is the identification of “levers”, which are resources requiring minimal investment but offering disproportionate impact. Guided by the Pareto Principle (where approximately 20% of inputs often generate approximately 80% of outcomes), leveraging these assets enables rapid wins and sustained progress through targeted, localised action.

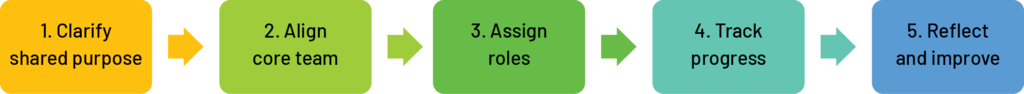

Figure 5 Co-action: Community mobilisation SOP

Community mobilisation (Figure 5) is the next phase of collaborative action, where residents collectively design and implement action plans informed by earlier data. The process begins with reaffirming the project purpose, to ensure focus, efficient resource allocation, and alignment among all participants.

A core mobilisation committee is then established, ideally comprising representatives from the 3P sectors with relevant expertise. Members from earlier committees may also join if they bring appropriate experience and commitment. Once convened, the committee reviews prior findings to build a shared understanding and sense of ownership.

Roles are then clearly defined, assigned, and documented using a stakeholder role map, which is a key toolkit for mobilisation. This prevents duplication, ensures accountability, and reinforces the principle that each member has a distinct contribution.

Progress monitoring follows, supported by mechanisms such as biweekly meetings for updates, troubleshooting, and sustaining momentum. Implementation is complemented by reflection and adaptation, with outcomes documented transparently. Reports should include resource use, including public funds, and can be disseminated formally and informally, such as through reports, social media, posters, or community boards.

The guiding principle of mobilisation is shared responsibility. When residents see the tangible impact of their roles, it fosters belonging, satisfaction, and long-term commitment, which are crucial for sustaining initiatives that require ongoing effort and maintenance.

3) Co-learning

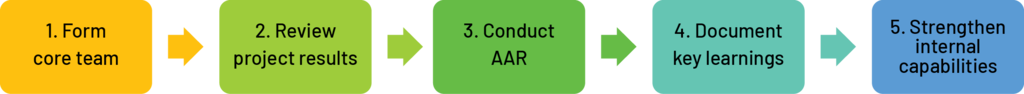

Co-learning refers to the collective reflection and learning process from the outcomes of a completed project. This phase ensures that experiences are retained, and future initiatives can benefit from accumulated knowledge. The primary tool employed during this phase is the after-action review (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Co-learning: After-action review (AAR) SOP

The initial step involves defining the purpose of the review and assembling a core team. It is crucial to establish a shared understanding that AAR is not intended to assign blame; rather, its aim is to foster a culture of learning and continuous improvement. This tone at the outset creates a safe and constructive environment conducive to honest reflection. The core team is then formed, comprising individuals who have participated in various stages of the project, including planning, execution, and monitoring. This diversity ensures that the review provides a comprehensive understanding of the project’s trajectory.

Once the review team is established, the second step entails gathering and reviewing all pertinent project results. This encompasses both quantitative data, such as participation figures or outcome indicators, and qualitative insights, including stakeholder feedback and community observations. Reviewing these materials prior to the AAR session facilitates the team in building a shared understanding of the project’s events, setting the stage for meaningful dialogue.

The key toolkit of AAR and third step involve conducting the AAR session using three guiding questions:

These questions provide a straightforward yet effective structure for discussion, enabling the team to acknowledge successes, identify shortcomings, and propose improvements in a constructive and forward-looking manner.

The fourth step entails documenting the key learnings that emerge from the session. Capturing these insights in writing ensures that valuable reflections are not lost over time. Proper documentation also enhances transparency, facilitates knowledge transfer, and contributes to an organisational memory that can inform future endeavours.

The final step involves strengthening internal capabilities. This can be achieved by developing an improvement plan based on the review findings. This plan should outline specific actions or changes to be incorporated in future iterations of the project. The results of AAR, including the improvement plan, are then shared with all relevant stakeholders. This step fosters accountability, promotes collective learning, and increases the likelihood of continued community participation and support.

By institutionalising learning through the AAR process, the community builds a culture of reflection, adaptability, and continuous progress. This stage not only ensures that each initiative delivers impact, it enables the rapid implementation of solutions, with each cycle of learning contributing to more effective and refined approaches. In this way, every effort both generates immediate results and strengthens a growing body of practical knowledge to guide future community-led initiatives.

To enhance the effectiveness, relevance, and sustainability of community development efforts in Singapore, it is crucial that organisations adopt structured yet adaptable frameworks that foster collaboration, ownership, and continuous improvement. The co-vision, co-action, and co-learning approach provides a practical roadmap for achieving this, enabling communities to collaborate, act, and learn together.

This ABCD model transcends a mere process; it represents a mindset shift. By integrating shared visioning, asset-driven action planning, and reflective learning into the design and execution of programmes, organisations can unlock deeper community participation, accelerate outcomes, and ensure that each project builds upon the previous one. I encourage practitioners across the 3P sectors to explore how this framework can be adapted to suit their unique contexts and communities.

In an environment characterised by rising expectations and limited resources, it is no longer sufficient to merely run programmes; we must co-create them with the communities they are intended to serve. By committing to the principles of co-vision, co-action, and co-learning, we can construct stronger, more resilient communities which possess the capacity to lead their own transformative journeys. This embodies the true Singapore spirit of “we”.

Related articles by Prof Ang:

Impact Measurement For Social Good (Part 2 Of 2)

Impact Measurement For Social Good (Part 1 Of 2)

Social Impact Bond

Restructuring Charities (Part 2)

Restructuring Charities (Part 1)

Social Entrepreneurship: ESG For Charities (Part 2)

Social Entrepreneurship: ESG For Charities (Part 1)

Professor Ang Hak Seng is Director of Centre of Excellence for Social Good, and Professor of Social Entrepreneurship, Singapore University of Social Sciences.

References

Ang, H. S. (2023a). Creating and Qualifying Social Impact Investments For The People Sector. IS Chartered Accountant Journal, October 2023, 26–31.

Ang, H. S. (2023b). Restructuring Charities: Impact Investment For The People Sector. IS Chartered Accountant Journal, September 2023, 12–19.