TAKEAWAYS

In an October 2025 article on CA Lab, “Best Practices Of Asset-Based Community Development”, I had introduced the Asset-Based Community Development (ABCD) framework as an emerging paradigm for community development within the Singaporean context. That article had covered the overview, principles and challenges of ABCD.

This article extends that discussion by moving from theory to practice. It elaborates on the practical toolkits and methodologies required to implement ABCD effectively, and examines how these can be applied to address a pressing social issue, namely, ageing in place. To illustrate this, we use the case of Marina Crest, a fictitious mature residential estate confronting the realities of Singapore’s ageing population.

Singapore’s demographic landscape is undergoing a profound transformation characterised by a steadily increasing proportion of older residents. By 2030, one in four citizens will be aged 65 years and above. This shift presents complex challenges for social policy, urban planning, and community cohesion, particularly in mature estates that were not originally designed to support senior mobility, accessibility, or intergenerational interaction.

Marina Crest, while fictitious, reflects the realities faced by many such neighbourhoods here in Singapore. It was “selected” as a pilot site due to its diverse resident profile, strong local identity, and established volunteer infrastructure. The Marina Crest Team was tasked with operationalising the ABCD framework to develop locally relevant responses to ageing in place and, through their review, three common challenges associated with traditional ABCD implementation were identified:

The following sections describe how the three principal phases of the ABCD process (Co-Vision, Co-Action, and Co-Learning) were implemented in Marina Crest, alongside summaries of the standard operating procedures (SOPs) that supported each phase.

The Co-Vision phase forms the cornerstone of the ABCD framework. It involves cultivating a shared sense of direction among stakeholders and developing a collective understanding of what constitutes “ageing well” within the local context.

However, implementation was not without challenges. The Marina Crest Team identified three recurring issues: managing competing stakeholder agendas, low public awareness of community needs, and risk aversion.

To address these, the Marina Crest Team adopted the Centre of Excellence for Social Good’s contextualised version of ABCD, beginning with two key components under Co-Vision, namely, community ground sensing and community visioning.

Community Ground Sensing

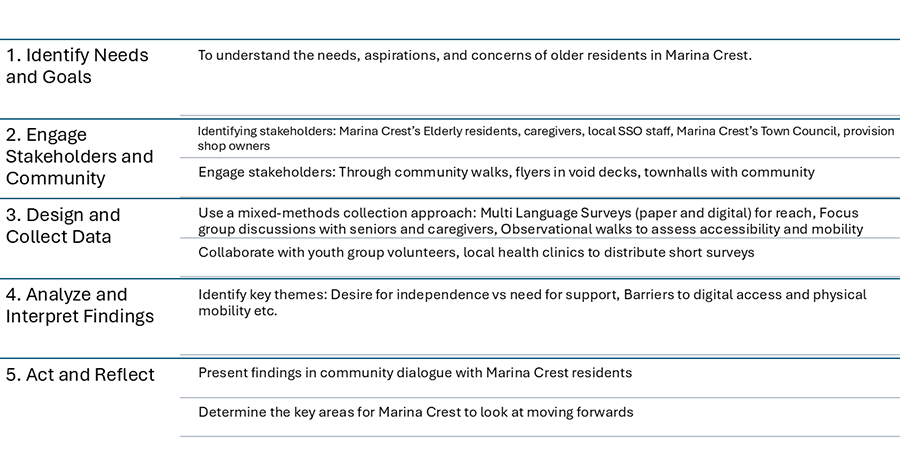

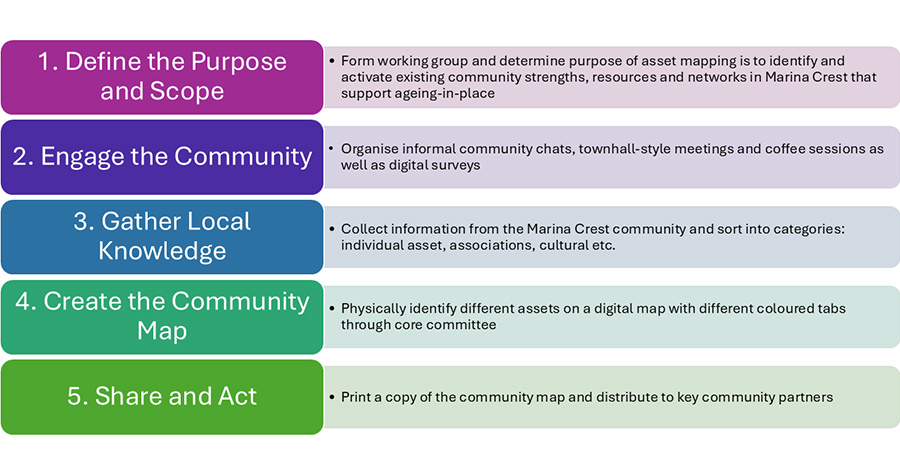

The first component of Co-Vision is community ground sensing, a structured exercise aimed at understanding residents’ lived experiences, values, and aspirations. To systematise this process, the Marina Crest Team developed a contextualised SOP based on the template SOP (Figure 1) (Ang, 2025).

Figure 1: Community Ground Sensing SOP

The Community Ground Sensing SOP provided a systematic and participatory approach to data collection, engagement and validation, thereby ensuring that insights were generated by and for the community. The key stages included were: (1) identify needs and goals, (2) engage stakeholders and community, (3) design and collect data, (4) analyse and interpret findings, and (5) act and reflect.

Two key toolkits supported this process: the CARE Framework and the Fishbone Chart. The CARE Framework, representing clear, attentive, respectful, and encouraging, was applied to facilitate genuine, trust-based engagement with residents and partners. Each component served a specific function:

This framework proved particularly effective in engaging Marina Crest’s seniors, many of whom were initially hesitant or sceptical about participating in formal consultations.

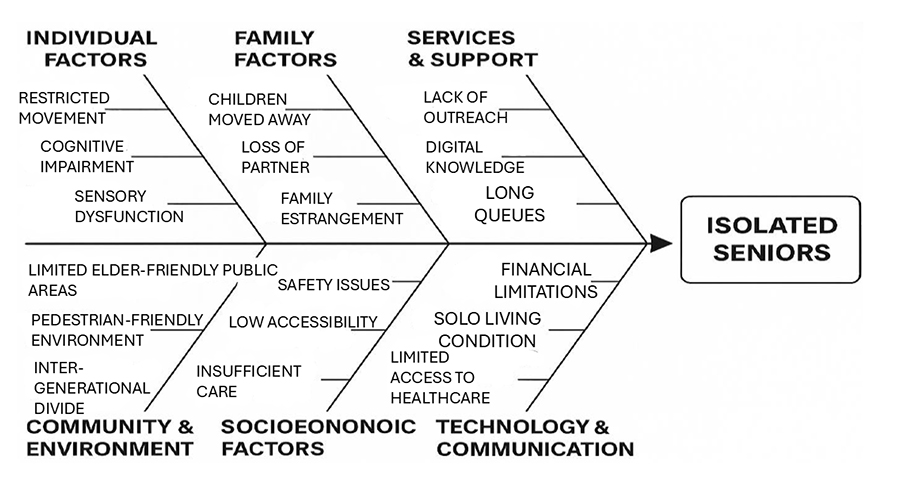

Complementing this, the Fishbone Chart (Figure 2) was used to explore root causes beyond surface-level symptoms. For instance, discussions on senior loneliness revealed deeper issues such as limited mobility, digital exclusion, and fewer opportunities for meaningful social contribution.

Figure 2: Fishbone Chart

Through structured dialogues and fishbone charts, several consistent themes emerged:

The findings were consolidated into a Community Brief, shared via townhall sessions, local networks, and online channels. This closing step reinforced a key ABCD principle – that insights generated within the community must be returned to the community for collective validation and shared reflection.

Community Visioning

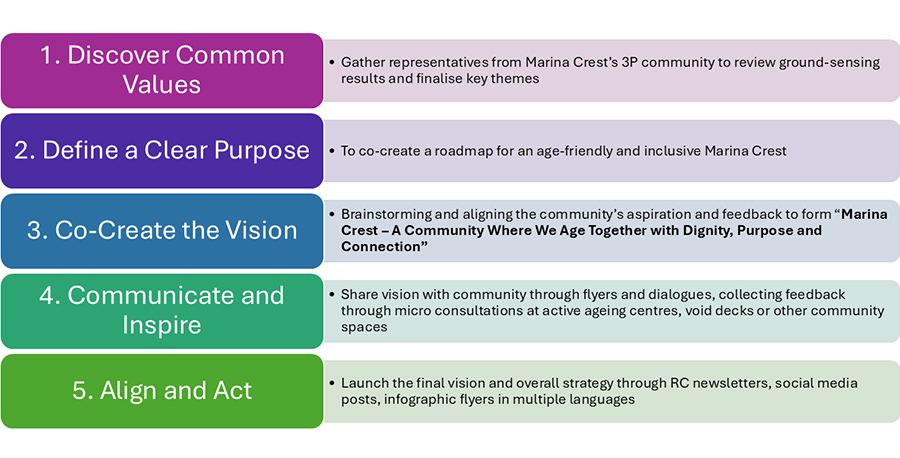

Building upon the findings from ground sensing, the second stage focused on co-creating a shared vision for ageing well in Marina Crest. To systematise this process, the Marina Crest Team developed a contextualised SOP based on a template SOP (Figure 3) (Ang, 2025).

Figure 3: Community Visioning SOP

The Community Visioning SOP guided the facilitation of collaborative workshops designed to co-create a shared vision. It emphasised neutrality, inclusiveness, and iterative feedback. This SOP has several key stages, namely, (1) discover common values, (2) define a clear purpose, (3) co-create the vision, (4) communicate and inspire, and (5) align and act.

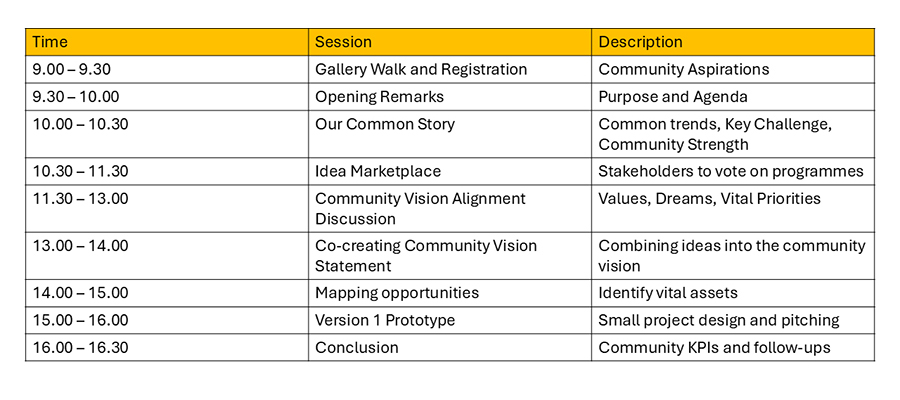

To co-create the community vision, the Marina Crest Team organised a Community Visioning Workshop (Figure 4) which convened residents, volunteers, local small and medium-sized enterprises, and representatives from the public and non-profit sectors. Rather than prescribing issues, the team presented observed community trends, enabling participants to frame challenges and design solutions collaboratively.

Figure 4: One-Day Community Visioning Workshop

Participants were encouraged to imagine an ideal Marina Crest that supports seniors to remain active, connected, and valued members of society. They discussed physical infrastructure, social relationships, intergenerational engagement, and inclusive spaces.

After multiple iterations and consultations, the community agreed upon a unifying statement: “Marina Crest: A Community Where We Age Together with Dignity, Purpose, and Connection”.

This shared vision, endorsed by community partners, subsequently guided the design and implementation of activities during the next phase.

The Co-Action phase focuses on transforming shared aspirations into actionable initiatives. It comprises two major processes, namely, Community Asset Mapping, and Community Mobilisation.

The Marina Crest Team encountered several difficulties during this phase, including unclear accountability, limited awareness of local assets, and administrative overload. These were addressed through structured SOPs and targeted toolkits.

Community Asset Mapping

Central to the ABCD philosophy is the idea that all communities possess assets such as human, institutional, and spatial, that can be activated to address shared challenges. The Marina Crest Team applied the Community Asset Mapping SOP to systematically identify and document community resources across three sectors: the people sector, the public sector, and the private sector (Figure 5) (Ang, 2025).

Figure 5: Community Mapping SOP

The Community Mapping SOP guided the facilitation of engagement sessions designed to co-develop the asset map. There are several key stages, namely, (1) define the purpose and scope, (2) engaging the community, (3) gathering local knowledge, (4) creating the community map, and (5) sharing and acting on the map.

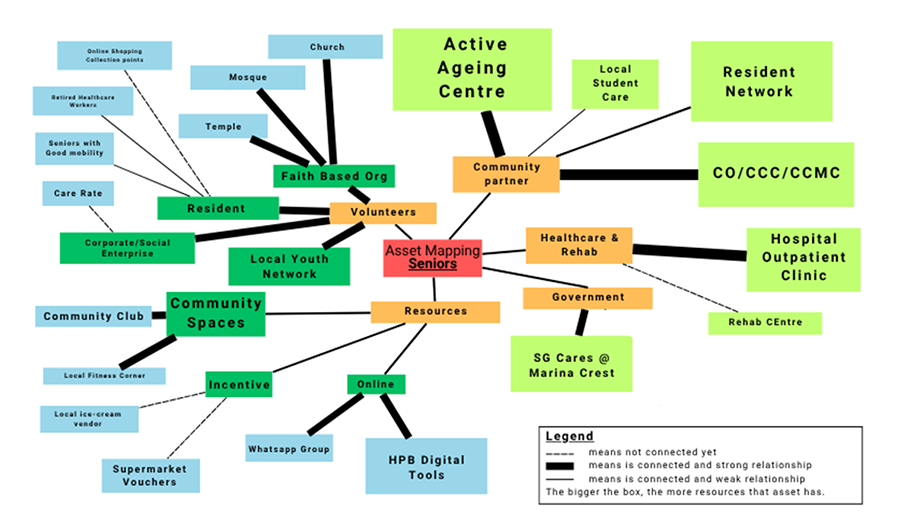

Beyond listing assets, the mapping exercise assessed relationship strength and identified strong, moderate, and potential connections. This helped surface key connectors capable of bridging networks (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Seniors’ Asset Map

Prominent assets identified included:

Together, these entities constituted a community ecosystem capable of delivering coordinated, resident-driven initiatives.

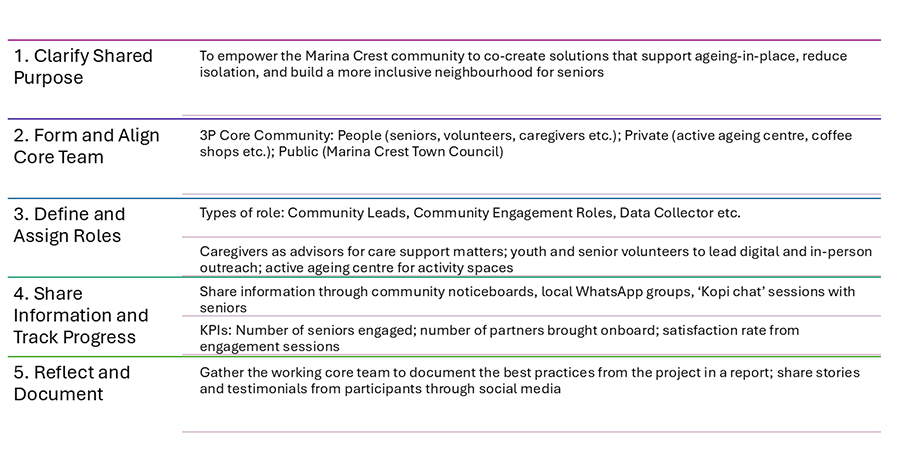

Community Mobilisation

Following the mapping of assets, the Marina Crest Team moved on to Community Mobilisation, which aimed to convert these identified resources into coordinated and sustained action. The SOP outlined a five-step process, namely, (1) clarify shared purpose, (2) form and align core team, (3) define and assign roles, (4) share information and track progress, (5) reflect and document (Figure 7) (Ang, 2025).

Figure 7: Community Mobilisation SOP

Two practical toolkits supported the mobilisation process: the Participation Map and the Gantt Chart.

The Participation Map was introduced to outline the process and define the roles of stakeholders across key tasks. It outlined three levels of involvement and ownership ranging from 1 (lowest) to 3 (highest): (1) I tell, (2) I involve, (3) I co-create.

The Gantt Chart provided a clear visual timeline of project milestones and dependencies. It allowed the team to coordinate multiple activities simultaneously, maintain momentum, and anticipate potential bottlenecks before they became obstacles.

Through the use of the Community Mobilisation SOP (which was adopted from a past template) (Ang, 2025) along with the toolkits, the Co-Action phase produced several measurable results:

These outcomes demonstrated that structured planning, inclusive engagement, and consistent communication are vital enablers of sustainable community mobilisation.

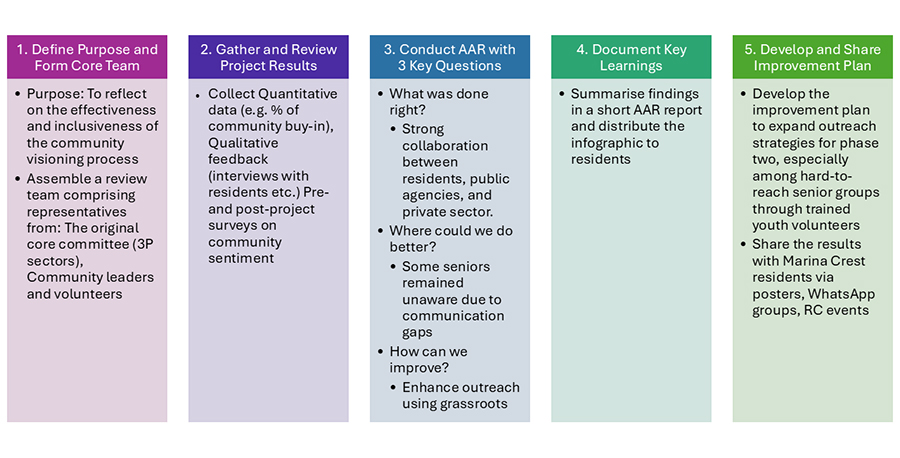

The third and final phase, Co-Learning, focused on collective reflection and adaptation. Rather than serving merely as a post-project evaluation, Co-Learning was designed as a continuous process that strengthened the community’s capacity to innovate and sustain progress over time.

Challenges such as volunteer turnover, inconsistent documentation, and pilot fatigue were addressed through a structured Co-Learning SOP (Ang, 2025). This included defining purpose, reviewing results, conducting After-Action Reviews (AARs), documenting lessons, and developing improvement plans (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Co-Learning SOP

The three guiding questions used during the AAR sessions were, “What was done right?”, “Where could we do better?”, and “How can we improve?”. It is important to start with “What was done right?” as beginning the review with positive reflections help set a constructive tone that encourages openness rather than defensiveness.

Through the AAR sessions, the Marina Crest Team uncovered several key insights, namely:

The regular conduct of AAR sessions transformed the initiative into a learning ecosystem, allowing continuous recalibration of approaches and preservation of institutional memory. To convert the new learning into new capabilities, it is essential to strengthen Marina Crest’s people, processes, and structure. By systematically examining these three aspects, the Marina Crest Team was able to restructure and enhance its approach for subsequent community programmes, ensuring sustained improvement and effectiveness.

The application of the ABCD framework in Marina Crest represented a significant shift in how communities approached complex social challenges. Rather than viewing seniors as passive recipients of care, the initiative recognised them as active contributors with valuable experience and social capital.

Although the process was gradual and resource-intensive, it demonstrated that structured participation and shared ownership can produce sustainable outcomes. Through deliberate engagement, careful coordination, and continuous reflection, the Marina Crest Team fostered a culture of mutual respect, empowerment, and collaboration.

The ABCD approach reframes community development as collective empowerment, stressing local ownership of issues and building resilient, inclusive communities. It encourages a “we first” mindset so residents can age with dignity and purpose.

Related articles by Prof Ang:

Professor Ang Hak Seng is Director of Centre of Excellence for Social Good, and Professor of Social Entrepreneurship, Singapore University of Social Sciences.