TAKEAWAYS

“Where have all the good jobs gone?”

Many reminisce about the jobs of yesteryear – a time when jobs were steady, handshakes were covenants, and a “fair day’s work for a fair day’s pay” was not just a catchphrase but a lived reality. History has a funny way of idealising the past. From the dawn of capitalism, there has been this collective sigh, a feeling that once upon a time, things were just … better.

And here we are, 21st-century folks, often feeling like mere cogs in an ever-accelerating machine, and nursing a fear of being left behind or replaced by a well-coded algorithm. Recent data show that Singapore workers are some of the most unhappy in the world, with pressing concerns about mental health and job satisfaction. It makes one wonder: Did our predecessors genuinely relish their 9-to-5 jobs more than we do? Or are we just riveted by the allure of nostalgia?

With World Mental Health Day observed globally on October 10, this is an opportune time for self-reflection, with a particular focus on our professional well-being.

Job satisfaction is not merely corporate speak. Instead, it can serve as an indication of the state of our mental health. The equilibrium we find in our professional life reverberates through our overall well-being. A consistent shortfall in job contentment not only fuels burnout and anxiety, it affects organisational outcomes like productivity and retention. Indeed, our professional well-being should be everyone’s business.

Data can often enlighten us where memory falters. The General Social Survey (GSS) offers insights into Americans’ job satisfaction from 1972 to 2021. Our deep dive into the GSS dataset has produced Figure 1, which highlights a fascinating observation: job satisfaction rates have remained almost consistent across these five decades, with minor fluctuations.

Figure 1

This forces us to challenge the age-old narrative that, if our past was not really that golden, why do we think it was? A detailed exploration of a past GSS dataset1, which contains various job satisfaction-related variables, reveals some compelling insights.

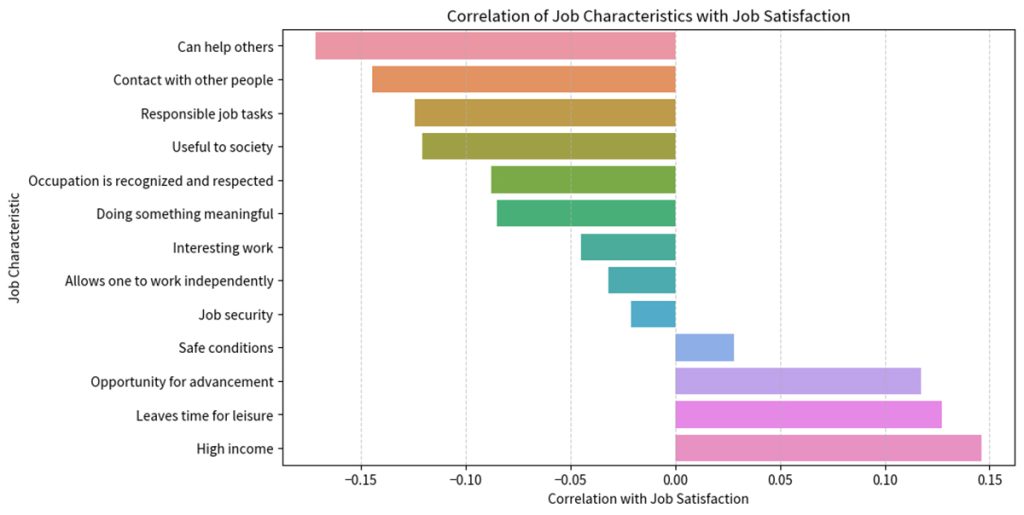

As seen in Figure 2, while the perceived importance of tangible benefits such as higher income and advancement opportunities positively correlates to job satisfaction, the perceived importance of less tangible factors such as human connection and societal contribution shows a negative correlation with job satisfaction. This could mean workers seeking purpose in their roles might be less satisfied with their jobs than their counterparts who are primarily motivated by money and success. But one must tread carefully here; just because two things are linked does not mean one causes the other. There could be other factors at play.

Figure 2

While not conclusive, this observation could shed some light on a puzzling situation. An article in The Economist states, “By any reasonable standard, work is better today than it was. Pay is higher, working hours are shorter, and industrial accidents rarer.” Yet, these tangible improvements have not necessarily translated into greater happiness. The true crux seems to lie in the intangibles: a sense of purpose, and a feeling of belonging.

Recent research, like PwC’s Global Workforce Hopes and Fears Survey – Singapore Highlights, echoes a similar sentiment. “Money isn’t enough by itself to retain workers, who were almost as likely to cite intangible factors related to meaning”, such as job fulfilment, having their viewpoints considered by their manager, and being themselves at work. Essentially, old certainties about what motivates people have changed.

Not long ago, we were deep into the “hustle culture” Silicon Valley championed. Then, to hustle was to succeed – waking up at ungodly hours, surviving on coffee, tied to desks – the grind was not just work, it was a lifestyle. Social media glorified this. In Singapore, a joint study, aptly named “Hustle Culture”, by Milieu Insight, a market research company, and Intellect, a Singapore-based mental health startup, shows that over half of the younger workforce embraced this grind. In the world of accountants, “peak seasons” are their version of the hustle – those intense times when they race against the clock to close financial books, prepare audits, and ensure compliance with tax regulations.

However, this “never enough” mentality has taken a toll. Mental health waned, personal relationships suffered, and job satisfaction hit rock bottom. The same study reveals that only 42% of Singapore’s workforce felt engaged, and 26% felt dissatisfied with their job. And while Singapore races ahead economically, over half of the employees reported a poor quality of life.

When the pandemic hit, it brought about a consuming inward contemplation of what truly constitutes job satisfaction. The ensuing “great resignation” was not only about changing jobs but about seeking deeper fulfilment and happiness. Various studies indicate that 40% to 75% of the global workforce contemplated leaving toxic work environments to prioritise work-life balance and, in Singapore, that figure stood at 49% for the latter half of 2022.

The ripple effects were also felt by the accountancy sector, with data from FloQast, an accounting software company, suggesting 53% of accountants were not entirely sure they would stay at their current company in the next year. Of these, 63% were not even sure they would stay in the industry at all, which points to a concerning talent shortage in the sector.

Amid this backdrop, a more subtle form of departure surfaced – the phenomenon of “quiet quitting”. In Singapore, 35% of the workforce and a staggering 55% of Gen Z have silently disengaged, doing just the minimum required. A report from Indeed, an employment website, pinpoints the leading causes in Singapore: feeling underpaid (45%) and burnout (44%). While accountants are not explicitly called out in the data, given the common perception of “overworked, underpaid” junior auditors and accountants, the statistics prompt questions about their levels of silent dissatisfaction.

As Gen Z enters the workforce, they are further reshaping its fabric. Born into the digital age, this generation possesses an acute awareness of global issues and societal inequalities. For them, job satisfaction is not solely about pay cheques, it is about contributing to a greater purpose. A Deloitte study validates this mindset, showing that Gen Z places less emphasis on salary compared to older generations. It states, “If given the choice of accepting a better-paying but boring job versus work that was more interesting but didn’t pay as well, Gen Z was fairly evenly split over the choice.”

For accountants, the picture is not rosy based on a survey conducted by CareerExplorer, a US career platform. It reveals that accountants rated their job satisfaction at only 2.6 out of 5, and a low 2.3 out of 5 when asked about finding meaning in their work. In such a landscape, the accounting profession must adapt to the evolving career aspirations of the younger generations.

For veteran CEOs and senior partners, the changing notion of job satisfaction is uncharted territory. In their playbook, climbing the ladder was the game. But Gen Z is not just looking upwards, they are asking what is holding that ladder, and why the climb matters. They crave depth, meaning, and broader horizons.

This is not just a hiring hiccup, it is a seismic generational shift. As traditional employers grapple to bridge this understanding, one thing is clear: the talent crunch is also a crunch of culture and values.

People today want more than just a job as they want to feel a part of something meaningful. They want to be loyal but loyalty is not a given, and it is earned when employers treat their staff right. As the job milieu evolves, loyalty thrives not just on pay cheques but on the deeper lexicon of engagement and purpose.

Let us pause for a moment and ask, “Why should employers care about staff job satisfaction?” The answer, simply put, is that when workers are happy, they stick around, give their best, and are less likely to jump ship at the first offer. The link between job satisfaction, lower turnover, and higher business productivity is underscored by statistical research; it is not just about contented workers but about thriving businesses.

Moving forward, employers may want to consider adopting a three-pronged approach to manage the new breed of employees:

1) Tuning in to your workforce makes a difference. Dive deep into conversations, such as using proactive “stay interviews”, and leverage human resource (HR) analytics to get an honest look at the employee landscape. Create an environment where voices are not just heard but actively sought. It is about ensuring workers genuinely believe their concerns will be addressed.

2) Then there is measuring. An unsettling gap exists between employer and employee perceptions. When 68% of leaders think they support mental health but only 41% of staff concur, there is an obvious missing link. You cannot improve what you do not measure. Employers need to find and employ tools that accurately gauge the pulse of their workforce.

3) Lastly, adaptation. Bain’s research vividly depicts employees not as a monolith but as a spectrum. From “pioneers” seeking to change the world to “artisans” aiming to hone a specific skill and “givers” desiring to make a direct impact on others, employees wear many hats. Recognising these varied aspirations and goals, employers will need to customise their engagement strategies.

As times change, so does our understanding of a “good job”. Each generation, with its own ethos, redraws the blueprint, and today’s workforce prioritises purpose, meaning, and holistic well-being over traditional metrics. In this fierce competition for talent, companies must think beyond the pay cheques to consider the whole work experience. The bar to satisfy has risen infinitely higher.

And herein lies the tension. While employees pivot to this new paradigm, many employers are found lagging, anchored in past practices. This dissonance rings loudly in the lament, “Where have all the good jobs gone?” In reality, it is not that good jobs have disappeared but that our expectations have shifted.

Guo Binglian is Research and Insights Manager, ISCA.

1 1982 data: the only year that job satisfaction-related variables were collected